One of the most pernicious consequences – if primarily for the anti-Russia west – resulting from the Ukraine war, has been the unprecedented spike in fertilizer prices which among other things, has sparked a historic surge in food prices and collapse in supply chains around the globe, as we discussed in these articles published over the past few months:

- Fertilizer Prices Hit Record Highs, May Pressure Food Inflation Even Higher

- “Fertilizer Is Out Of Control” – US Farmers Ditch Corn For Soy To Save On Costs

- Poop-Boom: Manure Supplies Tighten As Fertilizer Prices Soar

- World’s Largest Fertilizer Company Warns Crop Nutrient Disruptions Through 2023

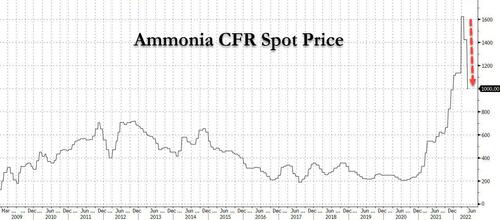

Fast forwarding to today, when we have some good, some bad and some pretty terrible news. The good news it that fertilizer prices have eased modestly from all time highs, as the following chart of Tampa Ammonia CFR spot prices shows.

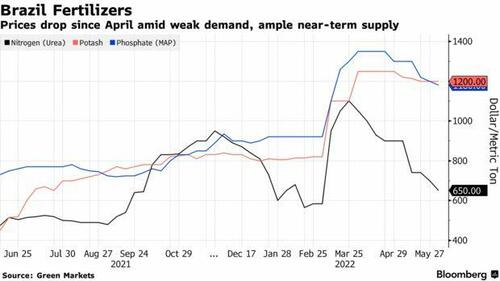

The bad news is that the the price hasn’t dropped nearly enough: according to Bloomberg, the glut of fertilizers piling up at the biggest Brazilian ports signals that the price of the nutrients has to drop further before farmers start buying.

In Paranagua, private warehouses reached their maximum storage capacity of 3.5 million tons, Luiz Teixeira da Silva, Paranagua’s operations director told Bloomberg. A terminal operated by VLI Logistics, one of the two at Santos port that store fertilizers, is also full, according to people with knowledge of the matter who asked not to be named as the information isn’t public.

As noted above, the price of fertilizers across the globe has exploded to unprecedented levels, and Brazil has been no exception.

That’s a problem because the agriculture-heavy country and food-source for half the globe, imports nearly 85% of its fertilizer and Russia is the main origin. As supplies have normalized, prices have declined over the past weeks, but farmers still aren’t buying. They are waiting for further price cuts, according to Marina Cavalcante, an analyst at Bloomberg’s Green Markets.

“Farmers have the expectation that prices will keep falling after declines last week and in the previous one,” she said. “So they’ll wait for further decreases to buy.”

And here is an example in supply/demand game theory: Brazil is the world’s biggest shipper of several crops, including soybeans. Farmers can delay their purchases until the eve of the soybean seeding in September. But if they all wait too long, a last-minute rush could lead to inland transportation bottlenecks that may leave some of them empty-handed anyway.

There is another problem: there just may not be enough actual fertilizer coming out of Russia, which has decided to punish the world by sending food prices for western nations to record highs and spark social unrest in the process. After all, the biggest reason prices are so high is because there is just not enough supply. And while speculators may have pushed prices somewhat higher than they should be, any farmers hoping that prices will fully renormalize will be disappointed.

Which leaves us with “demand destruction”, only as Rabobank’s Michael Every reminds us, when it comes to food “demand destruction” – especially at poor, third world countries – it has a different, less pleasant name: starvation.

Consider what is going on in Chad: as DW reports, Africa’s fifth-largest country declared a food emergency due to a lack of grain supplies. The landlocked African nation on Thursday urged the international community to help its population cope with rising food insecurity.

Cereal prices across Africa surged because of the slump in exports from Ukraine — a consequence of the war in Ukraine and a raft of international sanctions on Russia which have disrupted supplies of fertilizer, wheat and other commodities from both Russia and Ukraine.

DW spoke with one couple in Chad who are dealing with the effects of collapsing food supplies:

Cedric Toralta and Anne Non-Assoum live in the Boutalbagar neighborhood of Chad’s capital, N’Djamena. Non-Assoum — who had just returned from the market — expressed her dissatisfaction with rising food prices.

”Look what I bought: Here is meat for 1,500 CFA francs ($2.45, €2.28), rice for 1,000 and spices for 600 — that’s more than 3,000 CFA francs only for lunch for four people,” she said.

She told DW that in the past, the same purchase would have cost around 2,000 CFA francs. “My husband and I spent 60,000 CFA a month on food, but now, even 90,000 is not enough!”

The dire situation has forced Toralta to take drastic nutrition measures that are not without consequences.

“We can’t make ends meet, even though I decided to increase our food ration by 30,000 CFA francs. So I’m forced to reduce the amount we eat every day — and you see it’s affecting the children,” Toralta told DW.

”We need urgent food aid for the population,” Non-Assoum said, stressing the urgency. “If even the middle-income population in the capital can’t cope with this situation, how can the rural population? It’s very complicated, and we need the international community to help us.”

The prices of basic necessities have also risen significantly in Chad’s neighbor to the northwest, Niger. Milk, sugar, oil and flour are the products whose prices have skyrocketed there. The cost of fertilizer has also increased dramatically.

At a recent meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin, the African Union chairperson, Macky Sall, said the continent was bearing the brunt of the war in Ukraine due to a shortage of grain and fertilizer.

As a report from the ground (not from a well-fed Western journalist working from home) puts it: “In the village of Falke, some 665km (413 miles) from the capital Niamey, Tassiou Adamou, a farmer, told DW that this year’s harvest will likely be poor because producers cannot afford to buy enough fertilizer.

“Groundnuts, which are our main cash crop, need fertilizer,” Adamou pointed out. “Until last season, a bag of fertilizer cost 17,000 CFA francs. This year, it has reached 30,000,” he said, adding that it is impossible to produce much for those in the countryside.

“If you used to use three bags of fertilizer for your field, today, you can only have one bag with the same amount. Where you used to harvest 50 bunches of millet, you can barely produce 30 bunches without fertilizer.”

Much of Africa, Every writes, is in the same boat… and it is rapidly sinking, and the irony is that everyone needs much more fertilizer now to avoid a global food crisis, yet they either can’t afford it, or are hoping it falls some more in price. Unfortunately, that will not happen and instead marginal buyers will keep pushing the scarce commodity.

What happens next? We give the mic to Every, who summarized the current debacle best: “the global rich, who set rates, have to decide if they will sacrifice their asset prices to help the global poor eat. If we won’t say that, can we at least say that we have a choice between putting calories in rich people’s cars or in poor people’s mouths?”

To conclude, markets say “demand destruction”, but won’t say it can mean “mass starvation”. Some are now able to say “stagflation”, but many in markets weren’t allowed to until recently. Some can say “recession”, but many in markets and politics still aren’t allowed to. Yet nobody wants to say “depression” because there is *still* the assumption that, bad as things are, somehow a ‘hockey-stick’ bounce lies on the other side. Not sticks, stones, burning torches, and pitchforks.

Here, some may argue that “torches and pitchforks” is a euphemism, but put several hundred million people on food “demand destruction” for a few weeks, and watch as the next Arab Spring won’t be “Arab” and won’t be in the spring: it will be a Global Summer of starvation.